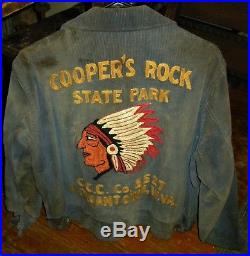

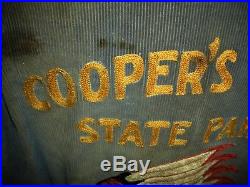

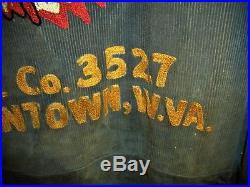

HERE IS AN AMAZING ANTIQUE 1930S CIVILIAN CONSERVATION CORPS JACKET FROM COOPERS ROCK STATE PARK CCC CO. 3527 MORGANTOWN WEST VIRGINIA. IDD TO GEORGE MORGAN. GREAT NATIVE AMERICAN INDIAN CHIEFS HEAD EMBROIDERED ON BACK. SOME WEAR FROM AGE & USE. THE BUTTONS SHOULDNT BE OPENED/CLOSED DUE TO CONDITION. THE ENDS OF THE SLEEVES ARE TATTERED. SEE PHOTOS FOR DETAIL. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a public work relief program. That operated from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men from relief families as part of the New Deal. Originally for young men ages 1825, it was eventually expanded to young men ages 1728. Was the first director of the agency, succeeded by James McEntee. Following Fechner’s death. The CCC was a major part of President Franklin D. That provided unskilled manual labor jobs related to the conservation and development of natural resources. In rural lands owned by federal, state and local governments. The CCC was designed to provide jobs for young men, and to relieve families who had difficulty finding jobs during the Great Depression in the United States. At the same time, it implemented a general natural resource conservation program in every state and territory. Maximum enrollment at any one time was 300,000. CCC-built bridge across Rock Creek in Little Rock, Arkansas. The American public made the CCC the most popular of all the New Deal programs. Sources written at the time claimed. An individual’s enrollment in the CCC led to improved physical condition, heightened morale, and increased employability. The CCC also led to a greater public awareness and appreciation of the outdoors and the nation’s natural resources, and the continued need for a carefully planned, comprehensive national program for the protection and development of natural resources. During the time of the CCC, enrollees planted nearly 3 billion trees to help reforest America, constructed trails, lodges and related facilities in more than 800 parks nationwide and upgraded most state parks, updated forest fire fighting methods, and built a network of service buildings and public roadways in remote areas. CCC workers constructing a road, 1933. CCC camps in Michigan. The tents were soon replaced by barracks built by Army contractors for the enrollees. The CCC operated separate programs for veterans and Native Americans. Approximately 15,000 Native Americans participated in the program, helping them weather the Great Depression. Despite its popular support, the CCC was never a permanent agency. It depended on emergency and temporary Congressional legislation and funding to operate. By 1942, with World War II and the draft. In operation, the need for work relief declined, and Congress voted to close the program. Change of purpose, 19371938. Conservation to Defense, 19391940. Decline and disbandment 19411942. Civilian Conservation Corps Museums. CCC notable alumni and administrators. Representation in other media. Vermont Youth Conservation Corps. Civilian Conservation Corps by state. Documentary, feature and TV movies. As governor of New York, Roosevelt had run a similar program on a much smaller scale. Long interested in conservation. As president, he proposed to Congress a full-scale national program on March 21, 1933. I propose to create [the CCC] to be used in complex work, not interfering with abnormal employment, and confining itself to forestry, the prevention of soil erosion, flood control and similar projects. I call your attention to the fact that this type of work is of definite, practical value, not only through the prevention of great present financial loss, but also as a means of creating future national wealth. He promised this law would provide 250,000 young men with meals, housing, uniforms, and medical care for working in the national forests and other government properties. The Emergency Conservation Work (ECW) Act was introduced to Congress the same day and enacted by voice vote on March 31. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6101. On April 5, 1933 which established the CCC organization and appointed a director, Robert Fechner. A former labor union official who served until 1939. The organization and administration of the CCC was a new experiment in operations for a federal government agency. The order indicated that the program was to be supervised jointly by four government departments: Labor. Which recruited the young men, War. Which operated the camps, and Agriculture. Which organized and supervised the work projects. A CCC Advisory Council was composed of a representative from each of the supervising departments. In addition, the Office of Education. Participated in the program. To end the opposition from labor unions (which wanted no training programs started when so many of their men were unemployed). Roosevelt chose Robert Fechner, vice president of the American Machinists Union. As director of the corps. Head of the American Federation of Labor. Was taken to the first camp to demonstrate that there would be no job training involved beyond simple manual labor. Reserve officers from the U. Army were in charge of the camps, but there was no military training. Was placed in charge of the program. But said that the number of Army officers and soldiers assigned to the camps was affecting the readiness of the Regular Army. But the Army also found numerous benefits in the program. When the draft began in 1940, the policy was to make CCC alumni corporals and sergeants. CCC also provided command experience to Organized Reserve Corps officers. Through the CCC, the Regular Army could assess the leadership performance of both Regular and Reserve Officers. The CCC provided lessons which the Army used in developing its wartime and mobilization plans for training camps. A CCC map of the planned route of a parkway in Texas, drafted in 1934. The Corps worked in numerous parks throughout the state during the early 1930s, constructing everything from benches to highways. The legislation and mobilization of the program occurred quite rapidly. Roosevelt made his request to Congress on March 21, 1933; the legislation was submitted to Congress the same day; Congress passed it by voice vote on March 31; Roosevelt signed it the same day, then issued an executive order on April 5 creating the agency, appointing its director (Fechner), and assigning War Department corps area commanders to begin enrollment. The first CCC enrollee. Was selected April 8 and subsequent lists of unemployed men were supplied by state and local welfare and relief agencies for immediate enrollment. On April 17 the first camp, NF-1, Camp Roosevelt. Was established at George Washington National Forest. On June 18, the first of 161 soil erosion. Control camps was opened, in Clayton, Alabama. By July 1, 1933 there were 1,463 working camps with 250,000 junior enrollees (1825 years of age); 28,000 veterans. 14,000 American Indians. And 25,000 Locally Enrolled (or Experienced) Men (LEM). The typical CCC enrollee was a U. Citizen, unmarried, unemployed male, 1825 years of age. Normally his family was on local relief. Each enrollee volunteered and, upon passing a physical exam and/or a period of conditioning, was required to serve a minimum six-month period, with the option to serve as many as four periods, or up to two years, if employment outside the Corps was not possible. Enrollees worked 40 hours a week over five days, sometimes including Saturdays if poor weather dictated. Following the second Bonus Army. March on Washington D. President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6129. (May 11, 1933) to amend the CCC program, to include work opportunities for veterans. Veteran qualifications differed from the junior enrollee; one needed to be certified by the Veterans Administration by application. They could be any age, and married or single as long as they were in need of work. Veterans were generally assigned to entire veteran camps. Enrollees were eligible for the following “rated” positions to help with camp administration: senior leader, mess steward, store keeper and two cooks; assistant leader, company clerk, assistant educational advisor and three second cooks. Inside of CCC barracks at Milford, Utah. Two of the men are sitting on footlockers that were used by the CCC workers to hold their personal possessions. Each CCC camp was located in the area of particular conservation work to be performed, and organized around a complement of up to 200 civilian enrollees in a designated numbered “company” unit. The CCC camp was a temporary community in itself, structured to have barracks (initially Army tents) for 50 enrollees each, officer/technical staff quarters, medical dispensary, mess hall, recreation hall, educational building, lavatory and showers, technical/administrative offices, tool room/blacksmith shop and motor pool garages. The company organization of each camp had a dual-authority supervisory staff: firstly, Department of War personnel or Reserve. Officers (until July 1, 1939), a “company commander” and junior officer, who were responsible for overall camp operation, logistics, education and training; and secondly, ten to fourteen technical service civilians, including a camp “superintendent” and “foreman”, employed by either the Departments of Interior or Agriculture, responsible for the particular field work. Also included in camp operation were several non-technical supervisor LEMs, who provided knowledge of the work at hand, “lay of the land, ” and paternal guidance for inexperienced enrollees. Enrollees were organized into work detail units called “sections” of 25 men each, according to the barracks they resided in. Each section had an enrollee “senior leader”. And “assistant leader” who were accountable for the men at work and in the barracks. Millhouse and waterwheel at Juniper Springs Florida built by the CCC. CCC workers with picks and shovels building road in Utah between Milford. The CCC performed 300 types of work projects within ten approved general classifications. Structural improvements: bridges, fire lookout towers. Transportation: truck trails, minor roads, foot trails. And airport landing fields. Check dams, terracing, and vegetable covering. Irrigation, drainage, dams, ditching, channel work, riprapping. Planting trees and shrubs, timber stand improvement, seed collection, nursery work. Prevention, fire pre-suppression, firefighting, insect and disease control. Public camp and picnic ground development, lake and pond site clearing and development. Stock driveways, elimination of predatory animals. Stream improvement, fish stocking. Food and cover planting. The responses to this seven-month experimental conservation program were enthusiastic. On October 1, 1933 Director Fechner was directed to arrange for a second period of enrollment. By January 1934, 300,000 men were enrolled. In July 1934 this cap was increased by 50,000 to include men from Midwest states that had been affected by drought. The temporary tent camps had also developed to include wooden barracks. An education program had been established, emphasizing job training and literacy. Approximately 55% of enrollees were from rural communities, a majority of which were non-farm; 45% came from urban areas. Level of education for the enrollee averaged 3% illiterate, 38% less than eight years of school, 48% did not complete high school, 11% were high school graduates. At the time of entry, 70% of enrollees were malnourished and poorly clothed. Few had work experience beyond occasional odd jobs. Peace was maintained by the threat of “dishonorable discharge”. “This is a training station; we’re going to leave morally and physically fit to lick’Old Man Depression,'” boasted the newsletter. Happy Days, of a North Carolina. Because of the power of the Solid South. White Democrats in Congress, who insisted on racial segregation, the New Deal programs were racially segregated; blacks and whites rarely worked alongside each other. At this time, all the states of the South had passed legislation imposing racial segregation and, since the turn of the century, laws and constitutional provisions that disenfranchised most blacks. They were excluded from formal politics. Because of discrimination by white officials at the local and state levels, blacks in the South did not receive as many benefits as whites from New Deal programs. In the first few weeks of operation, CCC camps in the North were integrated. By July 1935, however, all the camps in the United States were segregated. A total of 200,000 blacks were enrolled in the CCC; they served in 143 all-black camps. And received equal pay and housing. Black leaders lobbied to secure leadership roles. Adult white men held the major leadership roles in all the camps. Refused to appoint black adults to any supervisory positions except that of education director in the all-black camps. The CCC operated an entirely separate division for members of federally recognized tribes. The Indian Emergency Conservation Work (IECW or CCC-ID). Native men from reservations worked on roads, bridges, clinics, shelters, and other public works near their reservations. Although they were organized as groups classified as camps, no permanent camps were established for Native Americans. Instead, organized groups moved with their families from project to project, and were provided with an additional rental allowance in their pay. The CCC often provided the only paid work, as many reservations were in remote rural areas. Enrollees had to be between the ages of 17 and 35. During 1933, about half the male heads of households on the Sioux. Reservations in South Dakota. Were employed by the CCC-ID. With grants from the Public Works Administration. (PWA), the Indian Division built schools and conducted an extensive road-building program in and around many reservations to improve infrastructure. The mission was to reduce erosion and improve the value of Indian lands. Crews built dams of many types on creeks, then sowed grass on the eroded areas from which the damming materials had been taken. They built roads and planted shelter-belts on federal lands. The steady income helped participants regain self-respect and many used the funds to improve their lives. The federal Commissioner of Indian Affairs. And Daniel Murphy, the director of the CCC-ID, both based the program on Indian self-rule and the restoration of tribal lands, governments, and cultures. The next year, Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. Which ended allotments and helped preserve tribal lands, and encouraged tribes to re-establish self-government. Collier said of the CCC-Indian Division, “no previous undertaking in Indian Service has so largely been the Indians’ own undertaking”. Education programs also trained participants in gardening, stock raising, safety, native arts, and some academic subjects. IECW differed from other CCC activities in that it explicitly trained men in skills to be carpenters, truck drivers, radio operators, mechanics, surveyors, and technicians. With the passage of the National Defense Vocational Training Act of 1941. Enrollees began participating in defense-oriented training. The government paid for the classes and, after individuals completed courses and passed a competency test, guaranteed automatic employment in the defense work. A total of 85,000 Native Americans were enrolled in this training. This proved valuable social capital for the 24,000 alumni who later served in the military and the 40,000 who left the reservations for city jobs supporting the war effort. Responding to favorable public opinion to alleviate unemployment, Congress approved the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act of 1935. On April 8, 1935, which included continued funding for the CCC program through March 31, 1937. The age limit was expanded to 18-28 to include more men. From April 1, 1935 to March 31, 1936 was the period of greatest activity and work accomplished by the CCC program. Enrollment had peaked at 505,782 in about 2,900 camps by August 31, 1935, followed by a reduction to 350,000 enrollees in 2,019 camps by June 30, 1936. During this period the public response to the CCC program was overwhelmingly popular. Of April 18, 1936 asked Are you in favor of the CCC camps? ; 82% of respondents said yes, including 92% of Democrats. And 67% of Republicans. On June 28, 1937 the Civilian Conservation Corps was legally established, transferred from its original designation as the Emergency Conservation Work program. Funding was extended for three more years by Public Law No. Effective July 1, 1937. Congress changed the age limits to 1723 years old, and changed the requirement that enrollees be on relief to not regularly in attendance at school, or possessing full time employment. The 1937 law mandated the inclusion of vocational and academic training for a minimum of 10 hours per week. Students in school were allowed to enroll during (summer) vacation. During this period, the CCC forces contributed to disaster relief following 1937 floods in New York, Vermont, and the Ohio. And Mississippi river valleys, and response and clean-up after the 1938 hurricane in New England. In 1939 Congress ended the independent status of the CCC, transferring it to the control of the Federal Security Agency. The National Youth Administration. The Office of Education. And the Works Progress Administration. Also had some responsibilities. About 5,000 Reserve officers for the camps were affected, as they were transferred to federal Civil Service. And military ranks and titles were eliminated. Despite the loss of overt military leadership in the camps by July 1940, with war underway in Europe and Asia, the government directed an increasing number of CCC projects on resources for national defense. It developed infrastructure for military training facilities and forest protection. By 1940 the CCC was no longer wholly a relief agency, was rapidly losing its non-military character, and it was becoming a system for work-training, as its ranks had become increasingly younger, with little experience. Although the CCC was probably the most popular New Deal program, it never was authorized as a permanent agency. The program was reduced in scale as the Depression waned and employment opportunities improved. (the draft) began in 1940, fewer eligible young men were available. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor. In December 1941, the Roosevelt administration directed all federal programs to emphasize the war effort. Most CCC work, except for wildland firefighting, was shifted onto U. Military bases to help with construction. The CCC disbanded one year earlier than planned, as the 77th United States Congress. Operations were formally concluded at the end of the federal fiscal year on June 30, 1942. The end of the CCC program and closing of the camps involved arrangements to leave the incomplete work projects in the best possible state, the separation of about 1,800 appointed employees, the transfer of CCC property to the War and Navy Departments and other agencies, and the preparation of final accountability records. Liquidation of the CCC was ordered by Congress by the Labor-Federal Security Appropriation Act 56 Stat. 569 on July 2, 1942; and virtually completed on June 30, 1943. Liquidation appropriations for the CCC continued through April 20, 1948. Some former CCC sites in good condition were reactivated from 1941 to 1947 as Civilian Public Service. Camps where conscientious objectors. Performed “work of national importance” as an alternative to military service. Other camps were used to hold Japanese. Americans interned under the Western Defense Command. S Enemy Alien Control Program, as well as Axis prisoners of war. Most of the Japanese American internment camps were built by the people held there. After the CCC disbanded, the federal agencies responsible for public lands. Organized their own seasonal fire crews, modeled after the CCC. These have performed a firefighting function formerly done by the CCC and provided the same sort of outdoor work experience for young people. Approximately 47 young men have died while in this line of duty. The item “1930S CIVILIAN CONSERVATION CORPS JACKET COOPERS ROCK STATE PARK W VIRGINIA vafo” is in sale since Wednesday, October 25, 2017. This item is in the category “Collectibles\Militaria\WW II (1939-45)\Original Period Items\United States\Home Front”. The seller is “valleyforgeantiques” and is located in Downingtown, Pennsylvania. This item can be shipped to United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, Japan, China, Sweden, South Korea, Indonesia, South africa, Thailand, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Singapore, Switzerland, Norway, Saudi arabia, Ukraine, United arab emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Croatia, Malaysia, Brazil, Colombia, Panama, Jamaica.